| Home | Introduction | Contents | Search | Paintings | Essays | Interviews | Videos | Enquiries |

| DAMIEN HIRST | |

| Damien Hirst pages: Stole art • Excellent Painter • Reactionary Critics • Stuckist reviews • Hirst the Stuckist • Auction • Shark | |

| On this page: Damien Hirst the Excellent Painter |

|

This

article was published by 3ammagazine.com

27 November 2009. by Charles Thomson, co-founder of the Stuckists art group Damien Hirst has exhibited a series of remarkable paintings. They are remarkable for their depth and achievement, remarkable because Hirst, the hitherto superficial arch-conceptualist, has done them, and remarkable because they have been unanimously trashed by every critic in town.

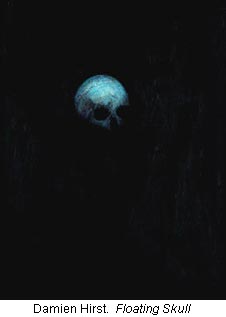

Isolation is the starting point of the spiritual journey The show, No Love Lost, at the Wallace Collection in London, is a spiritual odyssey, which starts with Floating Skull (1,1), the simple depiction of an isolated skull, the dome illuminated and the mouth lost in the blackness in which it floats. Hirst has likened this to a lonely planet, and, in reproduction, that is exactly how it appears. However, the gallery lighting - which I found appalling, but which is presumably deliberate - reflects beneath the skull off the otherwise-invisible, wide brushstrokes, which, as a result, looked to me just like visible wide brush strokes, though I have been told they look like water (and the skull presumably a fluorescent buoy). It ruins the effect of a distant planetary body and is a clumsy distraction from the essential content of a calm but isolated origin, whose potential remains to be revealed.

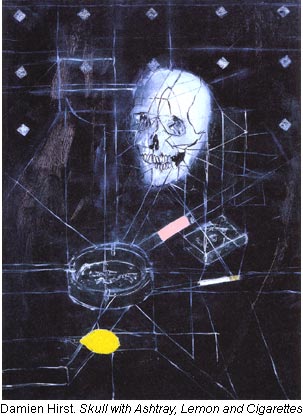

A self-portrait: this is the artist's inner world and, he insinuates, ours This potential begins to emerge in some small works measuring 24" x 16", where the skull is set in a simple context of thin lines or rows of small circles. These cautious forays gain in confidence, direction and complexity in bigger paintings, measuring up to 40" x 30", the most significant of them on the opposite wall to the small works. A key development is the outline of a table top in the bottom half of the canvas. This gives a geographical location, suggestive of the home or studio environment of the artist. The skull is not one of a corpse, but a self-portrait, demonstrating that externals have been stripped away and we have entered the artist's inner reality, where the material world is experienced more as a phantasm than a solidity, as shown by the thin outlines of an ashtray or cigarette packet resting on the equally insubstantial table. The skull's sardonic expression in Skull with Ashtray, Lemon and Cigarettes (11, 4) inquires if we recognise that this is our reality as well. The technical painting of the skulls is a combination of suggestion and definition. Ambiguous marks could be either sockets or eyes, and it is the viewer's state of mind which will make the interpretation. An obviously discordant feature is the bright yellow shape of a lemon. It undermines the nihilistic complacency of the proposition that the world is merely spectral, with a vividness of colour testifying that the material reality of the senses cannot be so easily discounted. It poses the question of how two such seemingly different dimensions can co-exist, but does not find a resolution. The yellow paint works aesthetically because it has been applied with just the right touch to leave a slight coarseness round the edges. The cigarette in Skull with Ashtray, Lemon and Cigarettes (11, 4) is delicately captured, whereas the pink lighter is a crude rectangular layer of paint which fails to evoke its subject, and remains just paint in a pink rectangle. Some of the backgrounds have an unusual effect like a blackboard covered with the misty remnant of wiped chalk. The top area of the paintings is marked out decoratively with restrained rows of circles, dots or diamonds. White lines animate the surface, while evidencing the attempt to make sense of reality by searching for connections within it. The untroubled void of empty space in the first painting in the show has been animated by the yearning to find meaning. The lines are evocative, when they are applied with focused care: the best in this respect are Small Skull with Lemon and Ashtray (12, 2), Skull with Ashtray, Lemon and Cigarettes (11, 4) and particularly Glass of Water and Ashtray (14, 8). Hirst is a psychologically accurate painter and succeeds technically when he paints with deliberation, but lacks virtuoso technique, and even small deviations into showmanship fall short. (A disastrously slapdash, but fortunately small, painting, Skull (13, 19) from 2008, on the far end wall of the room shows how easily he can lose his way.) A projection of lines in a pie-slice shape coming out of the skull in Skull with Ashtray and Lemon (10, 3) is a spindly irrelevance, which, along with a misjudged small diamond interrupting the vertical line to the right of the skull, is a weakness in an otherwise strong painting. Skull with Ashtray, Cigarettes, Lighter and Shell (9, 5) culminates in a frenetic rationality with a maze of lines, which threaten to annihilate any coherence. It is unfortunate that this effect is undermined by poor application, so the psychological impact of the lines takes second place to the lazy white paint marks and the inept outlines of rectangles and diamonds they define. The delicate tints of the shell, though, hint at a direction which could be explored further. A less insightful individual and less disciplined artist might well have been captivated by the attraction of this mesh of lines and developed it into further abstraction. This is the point where art becomes artificial and divorced from purposeful engagement. It is very much to Hirst's credit that he dismisses such temptation in his works, and instead develops forms which are a visual representation of inner states. The paintings described so far (apart from Skull (13, 19)) were made 2006 - 2007. They certainly have interest and accomplishment, although there is at times a hit and miss quality to this. The following paintings from 2008 increase dramatically in size up to 80" x 51", and are a major achievement. However, on my first visit to the show, I felt they were not successful and wrote that they had "generally overstretched his abilities." It was only on my second visit that I could appreciate their classical and monumental presence, and even more so during a third visit.

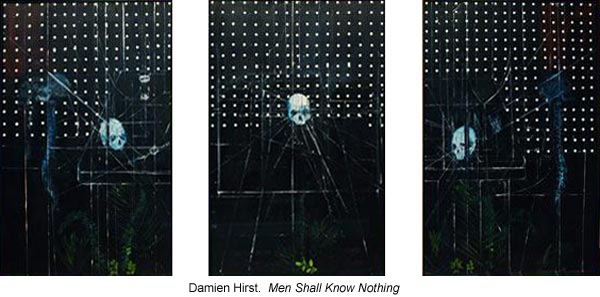

A masterpiece which reaches the limits of rationality and asceticism One series continues to use the central motif of the skull, and six of these paintings are arranged as triptychs, one such being Men Shall Know Nothing (19, 6), which has a skull in each of the three canvases and evokes the severity of a mediaeval monk's cell. Any excess in the earlier work has been shaved away; the skull represents humanity at the edge of mortality. The top half of each black-blue canvas is covered with a grid of white spots, which tap out a relentless pattern like the clockwork passage of time, making measurement but not meaning. The barely, but neatly, defined table top recurs as a symbol of the domestic interior. The smudged traces of disconnected spinal columns bookend the triptych, and hints of dark green foliage at the bottom of each picture are a reminder of a remote world of nature. The white lines have the fineness of scalpel cuts, running vertically like scratches on an old film, or radiating with nervous energy from the central skull with the precision of radio waves sent into space but failing to find reciprocation from any distant form of life. There is nevertheless a strong feeling of self possession and resolution, derived from taking the path of self-denial to this extreme, and learning that there is nothing more that can be gained from travelling further along it. It is a statement of both the structure and also the limitation of the rational, a mode associated by Jung with the masculine. It shows the circumscription of the conscious mind. The triptych is a masterpiece, and states memento, not mori, but that enlightenment cannot be gained from asceticism and logic alone. Its achievement is equalled by The Meek Shall Inherit the Earth (2, 7), the other triptych, also monumental and even more spare, consisting primarily of a skull in each painting (and an additional object, a shark's jaw, in the right hand painting) with spectral white lines, which seem on the point of dematerialising along with the occasional faint objects they indicate - a table top, a glass, a beetle, and, at the bottom of the central painting, what looks like a death mask in an embryonic sac, barely discernible and even less so in reproduction. (It is worth mentioning that many of these paintings do not reproduce well and the dark shades lose much of their presence in print form.) The acceptance that men shall know nothing appears to have led to the abandonment of the attempt to know anything. There is no grid of relentlessly ticking dots, no hazy spinal columns or hints of vegetation, just white, enervated, diagonal and vertical threads, which create varied divisions of the quiet darkness of the picture surface. The imbalanced composition denies the usual view of the triptych form as a flanked central motif and forces instead the reading of it as a storyboard. The malformed circle of the shark's jaw in the right hand painting resembles the lips of a mouth that opens to speak, but has no voice. It may or may not have an answer or know a passage to a more fecund place, which may or may not exist as only its absence has been proven so far. There is no anger or passion in this work, only a quiet and humble acceptance of a state of isolation, which Jung identified as an essential rite of passage. The title of the work asserts that what might seem like desolation we should in fact see as patience and expectation. Other paintings in this series are of less significance, being subsidiary explorations of similar themes. They incorporate a skull, an iguana, and a shark's jawbone. Whereas the use of gridded spots is a masterfully transformative quotation from Hirst's earlier conceptual work, the shark jaws do not always transfer so well into two dimensions, sometimes sitting uncomfortably in the composition as the remnant of old habits. Skull, Shark's Jaw and Iguana on a Table (21, 13) passes muster, while the neighbouring work, Shark's Jaw, Skull and Iguana on a Table (23, 14) is near-identical, but with the components clumsily pushed together. Iguana with Skull and Shark's Jaw (22, 16) repeats the arrangement, but with a second row of teeth in the middle of the open shape of the shark's jaw, so that it looks as though somebody had accidentally used Photoshop's cloning tool. It is a failed clever idea of the kind that Hirst needs to avoid. When he does, as in Shark's Jaw and Iguana (24, 15), he again achieves an enduring image, albeit a tad weakened by his decision to colour the lizard's tail with Naples yellow. This is also done in the previous three paintings mentioned, where it is even more out of place, an arbitrary intrusion, not being justified either in terms of meaning or aesthetics, and representing only another unsuccessful tentative attempt at a bravura touch.

The confrontation with pagan power antipodal to western Christian culture A dreamy, wistful and folklorish medium size painting, Woman of the Woods (3, 21) is in a completely different, soft, subdued, suggestive style, which, the title lets us know, is in the realm of the feminine, or more specifically, in Jungian terms, the anima. The gentle encounter with the woman of the woods is the innocuous introduction to a set of four large works, which, though figurative, seem at first sight to be straight out of the studios of Abstract Expressionism, but of a dark intensity, which makes most works of that school look like kindergarten colouring books and even Rothko's sombre effusions lightweight in comparison. The large skull-themed paintings of a conscious, Christ-less, Christian, ascetic and rational spirituality have here their counterbalance in the potentially overwhelming confrontation with a primeval, pagan and instinctive power from a mostly inaccessible and unconscious domain. In The Birth of Medusa (4, 24), the trunks of trees rise to the top of the painting like flames turned to ice, while a shape in the centre of the image is roughed in with a raw red, suggestive of some corporeal vestige, a bloody embryo or a flayed heart. Thin lines descend like white hot wires. A dark vertical stripe bisects the painting (as it does with the three companion paintings) like a dark generative power from - or a narrow doorway to - an even denser primordial level. When I first saw it, I forgot the genteel surroundings of the museum and entered the reality of the painting to be struck by a moment of fear. Either side of this painting are Guardian I (6, 25) and Guardian II (7, 23). Both are more complex than The Birth of Medusa and contain the vestiges of the grid of spots which the central painting does not have. More disturbing is the apparition in Witness at the Birth of Medusa (5, 22), where the barely-discernable form of the witness is almost effaced by shredded trees and incessant vertical lines like razors slashing the air and dismembering the comprehension of the figure in the face of what he encounters. The v-shape of what appears to be the beating wings of a bird are above him, either descending with unseen claws about to sink into invisible eyes or arising as the dark messenger of what has been witnessed. At the bottom of the picture there is the faintest outline of a table and an ashtray. The witness is the artist and the setting is where it has been all along, in the familiar everyday, which almost disintegrates in this near-psychotic storm.

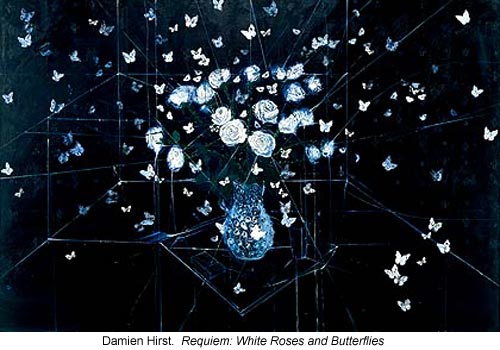

The resolution of a spiritual journey, the cosmic in the mundane Hirst has already declared an agenda of "going more towards Rembrandt and away from Bacon". Rembrandt is noted for his integration of darkness and light. At the end of the show, Hirst's Requiem, White Roses and Butterflies (25, 20), celebrates the grail won at the end of a spiritual odyssey, or, in the Jungian schema, attainment of the self, a state of mind which maintains a balanced dialogue between the ego and archetypal unconscious drives. The continuation of the colours of dark blue and white relate the painting to the rest of the exhibition. The starting motif of the skull has been transubstantiated into a spray of white roses in a vase, which takes its place alongside settled outlines of a glass of liquid and a cigarette packet on a table top. The constellation of butterflies across the dark depths of the background creates the effect of a star-filled sky, or the emanative force at the creation of the universe. It is a visual equivalent to Blake's "Auguries of Innocence":

After the bleak purgatorial journey and the dark night of the soul, where everything non-essential was stripped away and fearsome power was encountered face to face, it is a celebration of joy, beauty and wonder, a spiritual healing and illumination, a requiem for the death of death. Hirst's previous conceptual oeuvre stands in contrast to this work as a series of studies for it - literally the concepts which now inform his paintings, where the infinitely more subtle and flexible capability of paint is able to bring his meaning into fruition with a previously unachievable clarity and force of expression. In order to do this, he has on the whole wisely recognised as a painter his limitations, within which he has defined and mastered the approaches and motifs necessary to realise a highly focused vision. This is not the end of the journey, or even the map for it, but rather a first step from one stage of personal and artistic life to the next. As an initial body of paintings it is an outstanding achievement. The numbering in the book "No Love Lost" differs for most paintings from the show numbering. The numbers in brackets show the book number first and the show number second. |