| Home | Introduction | Contents | Search | Paintings | Essays | Interviews | Videos | Enquiries |

| DAMIEN HIRST | |

| Damien Hirst pages: Stole art Excellent Painter Reactionary Critics Stuckist reviews Hirst the Stuckist Auction Shark | |

| On this page: The Art Damien Hirst Stole |

|

This

article was published by 3ammagazine.com

4 December 2009. by Charles Thomson, co-founder of the Stuckists art group Damien Hirst's show of paintings, No Love Lost, at the Wallace Collection has been greeted by near-universal critical condemnation. The critics are wrong. They are stuck in fossilised values, which Hirst has outgrown.

It takes the Stuckists to point to the worth of Hirst's paintings, as the critics don't get it The critics' parameters are the still-flailing tail end of the 20th century paradigm of progress, where newness was seen as a desirable quality for its own sake and automatically deemed to be beneficial. Other significant contributory factors during this period were increasing specialisation, obsession with the material, and belief in scientific rationality raised to a religious status. The inevitable outcome of these forces was Modernism's ever-increasing artificiality, superficiality, sensation-seeking, and self-destructive tendencies, reaching an apotheosis, when they were magnified into Postmodernism with a disillusionment which added cynicism, the cult of the celebrity for celebrity's sake, and wealth as a substitute for worth. The depreciation of content and meaning in favour of innovation led to a specious finale of gimmickry and senseless sensation, and the more the real worth of art diminished, the more its status and market value inflated. Hirst exploited such predilections with unerring acumen for two decades, becoming the world's richest ever artist by making the world's worst ever art. He not only recognised this, but openly declared it, setting in 1990 an agenda "to get into a position to make really bad art and get away with it," saying in 2000 of his spin paintings, "They're bright and they're zany - but there's fuck all there at the end of the day," and in 2004 titling a catalogue essay for Tate Britain: Why Cunts Sell Shit to Fools. Such denunciations were acceptable as an ingredient of the expensive cheap thrill he packaged, as long as he also continued to provide security by dutifully playing his part in the circus along with everyone else.

Damien Hirst may not realise that he is now a Stuckist What was not acceptable was the integrity which led him to reject a fa็ade he had outworn, and, as his New York gallery put it, "kill the golden goose", when last month he not merely asserted, but put into practice, the same understanding that the Stuckists had embodied since 1999, condemning hedonism, dismissing conceptual art as a "dead end" whose products were "shit", promoting painting as an intimate and psychologically transformative mode of expression, and stating that artistic success is brought about not by technical virtuosity but through enterprise and courage. For good measure he paralleled the Stuckist aversion to white wall galleries and spoke similarly of a lineage back to cave art. A sly ironic spin placed on all this would easily have allowed him ample wriggle room to continue his top-end joke shop brand, but he compounded the heresy - as had the Stuckists before him - by making it clear that he was deadly serious, and he has consequently been treated by the art establishment with the same hostility they have previously meted out to the Stuckists. Damien Hirst has, in fact, become a Stuckist, whether he knows it or not. Jonathan Jones: Hirst is "savagely conservative", Stuckists are "enemies of art" The Guardian art critic, Jonathan Jones, became incandescent in pointing out that Hirst's volte-face was the depth of treachery:

Damien Hirst it turns out, is a savagely conservative critic of the art of our time. He's leading the backlash - against himself In his eyes, it would seem that all the readymades, all the vitrines - all the ideas that have made him rich - are not real art at all. They are substitutes for the art he wishes he could make. The one truly great art, in his eyes, is the high western tradition of oil painting ... an entire age of the readymade stands accused by its own creator of being a charade. No critic has even come close to the total dismissal of 21st-century art implied by Hirst's turnabout. This call to order leaves me dumbfounded. This

was a paraphrase of what Jones had written with similar rage under a

month previously about the Stuckists:

Adrian Searle: Hirst is "hubristic" and the Stuckists are "ranting" Adrian Searle, Jones' fellow critic at The Guardian, condemned Hirst for being "hubristic, and, at his worst, "amateurish and adolescent", having in the past condemned the Stuckists as "dreadful" and "ranting". Brian Sewell, fighting the corner for the 17th century, savaged Hirst's "puerile and maladroit paintings" and declared his "detestable exhibition fucking dreadful." Sewell had already put on record that "Stuckism is fundamentally silly. No Stuckist is worth a second glance or even a first." Matthew Collings: Hirst is "lightweight kitschy", Stuckist art has "no intensity" Broadcaster and critic, Matthew Collings, scorned Hirst's "lightweight kitschy works", whose "laughable signs of greatness include pseudo-scientific diagrams" and which show "Hirst's failure to be any good as a painter." Less than four weeks later, Collings was equally dismissive of Stuckist works: "They had no intensity at all as art, and no identity as paintings. They were cartoons that happened to be done in paint on canvas." Rachel Campbell-Johnston, art critic at The Times, was scathing about Hirst's show:

These works are utterly derivative of Bacon (give or take a dash of Giacometti), but they completely lack his painterly skill. And their metaphors are as ham-fisted as the application of pigment.They are, she concluded, "shockingly bad". Her sentiments are virtually interchangeable with those she had previously expressed about the Stuckists:

Some of the Stuckists who have recognised the quality of Damien Hirst's paintings I initially visited No Love Lost with Jo Pullar, a Stuckist artist and founder of Space 109 in York, and, allowing myself to talk intuitively and spontaneously about the first painting we looked at, Small Skull with Lemon and Ashtray, I found I was praising it enthusiastically. "I can't believe I'm saying this about Damien Hirst," I said to her. Still doing a double take on my own reaction, I became even more surprised when other Stuckist artists, such as John Bourne, Mark D, Paul Harvey, Edgeworth Johnstone, Shelley Li and Nick Christos, as well as Fraser Kee Scott (director of A Gallery and partner in Wanted Gallery) - whom I subsequently visited Hirst's show with or asked about it - were also positive, some of them extremely so, in their response. The polarisation of opinions about Hirst's and the Stuckists' work is symptomatic of a paradigm shift, something I attempted to explain recently to Matthew Collings in conversation in the bar after we had both taken part (on opposite sides) in a debate about conceptual art at the Oxford Union; but he did not believe me. Evaluation based on the matrix of ideas and perceptions of an existing paradigm will by definition fail to appreciate and understand work executed under the aegis of a new paradigm, which has reconfigured priorities, discarding certain previous imperatives and introducing other ones in their place.

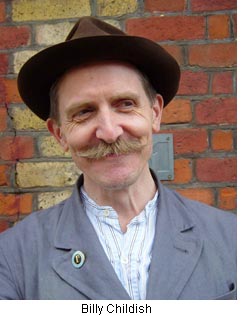

Billy Childish co-wrote the Remodernism manifesto with Charles Thomson in 2000 The 20th century paradigm was one of progress. The 21st century paradigm is one of conservation. In 2000, Billy Childish and I wrote a manifesto titled Remodernism, calling for a different response to Modernism, in contrast to the existing development of it into Postmodernism. Remodernism involves a valuation of things for their true worth, when viewed in a deeper and wider - that is, holistic - perspective beyond immediate considerations and appearances. It emphasises spiritual and ethical principles, and honesty in self-knowledge. It balances the demands of intellect and emotion. It relates psychological and material realities. It reclaims those things from the past, which we can still benefit from, but which have been rejected for spurious reasons. In art it abandons the clich้ of challenge, which has no value as a stand-alone prerogative. What is needed is not the undermining of standards, which have already been undermined, but the finding and affirmation of worthwhile ones. Meaning in art as part of critical assessment has all but been extinguished by the default to believe only in the lack of meaning. Meaning, content and communication bring art alive and justify its existence. Authentic ideas allied with truth to emotion and experience are the soul of art. Aesthetic consideration and technical means can be dictated sensibly only by the impetus of the content and can be judged rationally only in relation to it. The work needs to be experienced as a whole, and its success or otherwise assessed by the consciousness it evokes in the viewer. It is also necessary to address the media available for creative work: they are not homogenous, but have different characteristics and perform different functions. The resurrection of the superiority of painting by the Stuckists and by Hirst is neither accidental, whimsical, nor nostalgic. Hirst's paintings succeed because he recognises his technical limits and capabilities, within which he is able to attain a substantial creative achievement through a wholeness of inquiry, spirituality, humanity and emotion in the content. This does not seem to appear on the register for contemporary critics, who, one might suppose, have become so accustomed to the lack of any meaning that they are unable to read it within a work of art, which they are reduced to evaluating in terms of its technique and materials. Thus elements of Francis Bacon's paintings - such as a dark background or the use of lines - are seen to invalidate Hirst's work as derivative. This metric is in stark contrast to that applied where pre-Modernist works are concerned: Leonardo da Vinci's employment of chiaroscuro does not cause Rembrandt to be dismissed as derivative because he also made use of light and shade. He is understood to be using it in a different way and also introducing other elements into his work. Hirst uses lines in a different way and for a different purpose to Bacon, whose lines show off their mastery, yet are also more simplistic in their message and less suggestive, as they perform an architectural function. In contrast, Hirst's multitudinous lines are the evidence of his travel and demonstrate that he is seeking a deeper outcome than can be realised through instant definition. When Bacon paints dark backgrounds, it is to create isolation in a claustrophobic impenetrability. Hirst's have the stillness of contemplation, the power of an unknown to be explored, or even the mystery of immanence. Hirst has been deemed a bad painter, particularly in comparison with Bacon, yet the latter can employ the most gauche and obvious theatrical devices, as in Study after Velazquez's Portrait of Pope Innocent X, where the vertical streaks behind the figure are formulaic and those curving outward from him at the bottom of the picture are equally facile in striving for effect. If Hirst's work is compared on a purely technical basis with Bacon's later work, then Bacon is the clear winner in terms of innovation, demarcation of space, unexpectedness of colour and ingenuity of form, but his content falls far short of this standard of achievement.

Charles Thomson was bored by Bacon and absorbed by Hirst That this is not seen as a problem in critical evaluation reveals how devalued critical discourse has become. Art is about how something is done, but it is also about what is done. I entered last year's major Francis Bacon show at Tate Britain with interest and anticipation, which quickly turned to boredom. A fixation on pathology - in this case the mutilation of the human form - might be an interesting starting point at the beginning of an artist's career to set in motion a process of resolution and redemption, but its continuation, and indeed glorification, throughout a lifetime's oeuvre is the product of a dull spirit and a constricted mind. Virtuoso technique which embodies the mode of the moment and does not have enduring content can be seen, when the mode has passed, for what it truly is - a decorative craft. This is the reason why the fashionable academic artists of the 19th century have lost their value, and it is the reason why Bacon, a fashionable academic artist of the 20th century, will lose his. The taste of the late 1800s was for sentimentality and that of the late 1900s for cynicism. They are opposite but equal - and equally inhibited - visions. I remained absorbed in Hirst's show for a long time, engaged by his emotional depth and stimulated by the development of his intelligently enquiring creative process. He is a spiritual seeker whose odyssey we are invited to share. His paintings are a revelation of his inner being, and his enquiry is into the nature of existence. The realisation of this vision is what now validates him as an artist, although he has been condemned, while Bacon remains adulated, ironically, for the same false reasons that granted Hirst his former success. Mark Hudson in The Daily Telegraph said the critical backlash against Hirst was from:

people who really know their stuff: writers with an understanding of the art of all eras who have had to pander to every kind of money-inflated idiocy in order to appear relevant in our ever more uncertain cultural market place - in order, simply, to keep their jobs. That is something the Stuckists have been saying for the last ten years and as a result have been stigmatised as out-of-touch, deluded, ranting, conspiracy theorists. Hudson sees the critics' current stance against Hirst as proving that:

the world, or those aspects of it represented by the British media, retains a lot more integrity than many would have given it credit for. As

he has shown exactly how lacking in integrity these money-inflated idiocy

panderers, marching in lockstep, can be, and that whatever they have

said in the past cannot be trusted, I see no reason why we should begin

to trust them now. The critics got it wrong before by praising what

they should have condemned, and now they have got it wrong again by

condemning what they should have praised. The only integrity visible

is that of Damien Hirst, who has consistently spoken his mind, even

though people acted as if the implications of what he said did not really

matter - until he called their bluff.

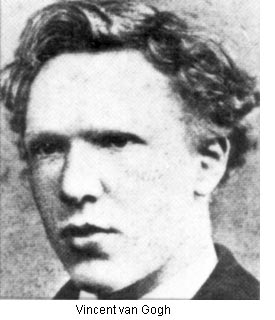

Van Gogh said a rudimentary artistic technique can be more communicative Hirst's painting is not bad; it is honest. As he put it himself:

Similarly, Vincent van Gogh wrote in a letter to his brother, Theo, on 21 July 1882:

See also: The

Art Damien Hirst Stole |